A

Literary Saloon

&

Site of Review.

Trying to meet all your book preview and review needs.

| Main |

|

| the Best |

| the Rest |

| Review Index |

| Links |

to e-mail us:

support the site

the complete review - literature / philosophy / psychology

What We See When We Read

by

Peter Mendelsund

general information | review summaries | our review | links | about the author

| Title: | What We See When We Read |

| Author: | Peter Mendelsund |

| Genre: | Non-fiction |

| Written: | 2014 |

| Length: | 419 pages |

| Availability: | What We See When We Read - US |

| What We See When We Read - UK | |

| What We See When We Read - Canada | |

| Que voit-on quand on lit ? - France | |

| Qué vemos cuando leemos - España |

- A Phenomenology

- Heavily illustrated

- Return to top of the page -

Our Assessment:

-- : flummoxing; colorful (in black & white) but doesn't dig very deep

See our review for fuller assessment.

| Source | Rating | Date | Reviewer |

|---|---|---|---|

| The NY Times | B- | 1/8/2014 | Dwight Garner |

| The Washington Post | D | 30/7/2014 | David Griffin |

From the Reviews:

- "Like a TED talk or a lesser Alain de Botton book, Peter Mendelsundís What We See When We Read is friendly and shyly philosophical, filled with news you can almost use. (...) Iíd like to be able to report that cracking and unpacking this exquisite package is a thoroughgoing joy. But What We See When We Read is so self-consciously charming that the senses frequently rebel." - Dwight Garner, The New York Times

- "What We See When We Read is a small, shallow pond of a book in which Mendelsund exhaustively swims around without ever going very deep. (...) I have a feeling that by including so many illustrations Mendelsund is punking the reader. (...) (T)his volume probably would have been better presented as a blog written in the form of easy-to-tweet missives (with visuals !)." - David Griffin, The Washington Post

Please note that these ratings solely represent the complete review's biased interpretation and subjective opinion of the actual reviews and do not claim to accurately reflect or represent the views of the reviewers. Similarly the illustrative quotes chosen here are merely those the complete review subjectively believes represent the tenor and judgment of the review as a whole. We acknowledge (and remind and warn you) that they may, in fact, be entirely unrepresentative of the actual reviews by any other measure.

- Return to top of the page -

The complete review's Review:

The French title asks 'What do we see when we read ?' but the English original makes its claim unquestioningly: this is meant to be a book about What We See When We Read.

That's a tall order, and Mendelsund doesn't dig nearly deeply enough to provide satisfactory answers.

Generalizations are always dangerous, and very little of what Mendelsund describes and claims corresponds to my experience.

Granted, I might be an outlier, reading-wise (though I don't think my experiences are that unusual).

As a consequence, it's difficult to review the book in any sort of objective manner; I can only see it from my perspective -- one of bafflement as great as if someone were telling me I was eating all wrong, and that nutrition shouldn't be consumed orally but rather intravenously (an argument that might, at a stretch, have some plausibility, but seems entirely absurd and certainly goes counter to all my personal experience).

He loses me right off the bat, with the assertions:

When we remember the experience of reading a book, we imagine a continuous unfolding of images.And:

We imagine that the experience of reading is like that of watching a film.And even as he argues that those aren't quite right, just starting from these premises -- not even softened by a 'we can' or 'we could', but insisting, absolutely, that 'we do' -- confuses the issues. (I certainly do not imagine reading as either of these things; it wouldn't even occur to me. Reading is, for me, an entirely different sort of mind-experience.)

Mendelsund -- an art director for a publisher, and well-known book-cover designer -- focuses specifically on the visual. Presumably, much the same applies to out other senses -- what we smell when we read ! -- but these rate only incidental mention. One non-visual example he gives is of reading out loud to his daughter, and she making him repeat a passage, once the identity of the speaking character was clear: "this time with a high, girlish voice appropriate to that particular character ..."; he argues that it's the same for picturing: "This is the process through which we visualize characters". Yet surely reading aloud is very different from 'normal' reading (i.e. not aloud), and the 'hearing' of the same passage very different when purely internal as opposed to performed. (Also: no, this is not 'the process' through which I visualize characters, and I imagine it would only be that for others if they were asked to draw the characters (the visual equivalent of reading aloud ?) -- something we are fortunately generally spared while reading.)

For someone like me -- as un-'visual' as it gets (unless they had explicitly been mentioned in conversation, I couldn't tell you the color of the hair, eyes, or clothes of a person I spoke to five seconds ago, much less describe them beyond the broadest outlines -- maybe (say, if they're notably tall, short, fat, etc.)) -- many of Mendelsund's claims and arguments are baffling: I simply do not 'read' this way. It's not merely the visual, either: my reading isn't sensory in the way he suggests: I don't hear, taste, smell, or feel in the way he suggests. Mendelsund allows for -- even insists on -- considerable fuzzyness, with a great deal of input by the reader ('imagining' looks, smells, etc., based on the written descriptions), but he still translates what is read into familiar sensory experience -- in the case of the visual, 'picturing' it.

Mendelsund seems, in particular, to think in pictures (largely ignoring, as noted, the other senses). He compares reading to film-viewing and suggests of a book, for example, that: "We simply remember it as if we had watched the movie ...". Yet my memories of books are nothing like those of watching movies -- in no small part because they unfold temporally so differently, even just in their consumption: I (try to) sit through the two hours of a movie, focused on it; I read a book over a few hours or days, with inevitable interruptions, and skimming back and forth. But even beyond the way they are consumed, the memory of the book -- except perhaps in the case of the most basic mystery or thriller ? --, in any form it is 'played back' or recalled in my mind, remains entirely different from a movie.

Too often, Mendelsund seems to see books like pre-comic-books: the words before the illustrations have been added. I've never really gotten comic books, because the pictures take away such a significant part of the reading-experience for me: showing me the way a character is meant to look lessens everything the character can be for me -- rendering them literally two-dimensional. And it's not because I can picture the character 'better' in my mind -- I can't picture the character at all, not in these terms, and yet s/he exist much more real-ly in my mind's eye without the supposedly helpful illustration. Mendelsund agrees with some of this -- "our visual memories are vague in general", he notes in discussing how we might picture Anna Karenina, and he admits our image may be: "Nothing so fixed -- nothing so choate". Yet he reduces and returns constantly to the pictorial.

What We See When We Read is a very visual volume: Mendelsund tries to make his arguments with illustrations as much as words. Many pages have very little text (and he shifts back and forth constantly between black text on a white surface, and white text on a black surface), and there are often corresponding illustrations. Sometimes this is effective: to demonstrate that, usually, when we read: "we do not apprehend words as we are reading them" he prints the four words: 'one at a time' over four pages (forcing us to read them one/at/a/time).

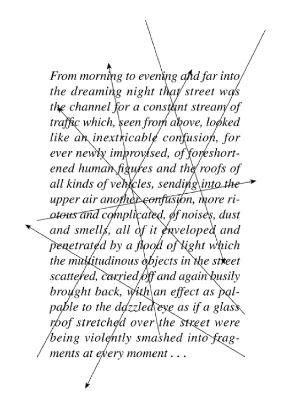

But too often his examples demonstrate the shortcoming of his thesis: he explains, for example, that: "When I am immersed in a book, my mind begins to formulate corresponding visual patterns", such as: "the vectors in Kafka's vision of New York City, from Amerika". The accompanying explanatory illustration is aesthetically attractive, but surely bears no resemblance to anything that could be going on in his mind, much less how he 'sees' this page. (If it does, then my 'ways of reading' are even more obviously completely removed from whatever it is he engages in.)

Can this be seen as -- indeed, is this -- anything but (would-be) clever word-(and-picture-)play, an art-director's game ?

Mendelsund suggests:

Doesn't reading a novel mean producing a private play of sorts ? Reading is casting, set decoration, direction, blocking, stage management ...Here -- as in a lot of other places -- he's onto something, but, as throughout, he doesn't explore much further. (His use of ellipses sums up the book very well, thoughts all left a'dangling .....)

Though books do not imply enactment in quite the same way that plays do.

To suggest the novel-as-(in-the-mind-)play is worth some consideration -- but, as throughout, Mendelsund's focus remains very much on the seeing -- and I'd suggest the process is a different one, a mind-manifestation that isn't so much visual. (I generally prefer reading playscripts to seeing plays staged -- in part, because the play isn't played out in my mind like on the satge: I don't 'see it' in my mind's eye; rather, reading it allows me to transcend the limitations of the visual and the aural, to focus on the piece an sich.)

Mendelsund reveals himself throughout the book -- no more so than in his claim:

But it is in a novel's phenomenology, the way in which a piece of fiction treats perception (sight, say), that a reader finds a writer's true philosophy.Surely only the philosophy the reader wants to find (or, in this case, so obviously is looking for). It's the treatment of 'perception' -- and, hey, what a surprise, coming from our ultra-visual guide: sight, say -- that's of foremost interest and concern to Mendelsund. Fair and interesting enough -- but he's so blind to the limitations he's imposing on himself -- his own inability to see beyond what seems to me a very limited way of 'seeing' -- that his book doesn't prove very insightful.

I've rarely found 'a writer's true philosophy' in their treatment of perception -- no doubt in no small part because I don't care that much. Yes, I notice it sometimes; yes, it does sometimes reflect on (what I see to be) the writer's philosophy. But I like to think I also look far beyond that -- and that that's a more rewarding way of reading.

So I found What We See When We Read flummoxing. Frustrating, too: it seems so obvious that there's more to 'what we see when we read' -- even if we choose to focus only on literal seeing, the visual. As is, this treatment feels very superficial -- ranging reasonably far, and with fun pictures, but not really probing.

Mendelsund's fully-illustrated text has some appeal -- particularly in the text-image pairings -- including, or especially, aesthetically. But even much of this seems to undermine his claims, the illustrations simplifications that demonstrate yet again that reading is a much more complex (and less-tied-to-the-visual) process than merely picturing things.

- M.A.Orthofer, 21 February 2017

- Return to top of the page -

What We See When We Read:

- Vintage publicity page

- Robert Laffont publicity page

- Seix Barral publicity page

- Excerpt

- Q & A at The New Yorker's Page-Turner weblog

- Q & A at The Rumpus

- amy reads

- Book Riot

- Boston Globe

- Brevity

- The Brooklyn Rail

- Collectif Carré Cousu Collé (French)

- culturamas (Spanish)

- en lisant en voyageant (French)

- Le Figaro (French)

- Fahrenheit 451 (Spanish)

- The Fault in Our Blogs

- Kate Forsyth

- The Globe and Mail

- Gràffica (Spanish)

- Kirkus Reviews

- Mercurio (Spanish)

- National Post

- Novel Conversations

- NYR Daily

- Pages & Pages

- Papel en blanco (Spanish)

- PopMatters

- Propeller Magazine

- Publishers Weekly

- Revista de Arte (Spanish)

- Revista de Libros (Spanish)

- Shiny New Books

- Sonder Books

- The Washington Post

- Jhumpa Lahiri considers The Clothing of Books

- See Index of Books on Books and Reading

- Return to top of the page -

Peter Mendelsund is an art director at Alfred A. Knopf.

- Return to top of the page -

© 2017-2021 the complete review

Main | the New | the Best | the Rest | Review Index | Links