the

Literary Saloon

the literary

weblog

at the

complete review

the weblog

about the saloon

support the site

archive

Arts Journal

Books, Inq.

BookRiot

Bookslut

BritLitBlogs

Con/Reading

Critical Mass

GalleyCat

Guardian Unlimited

Jacket Copy

The Millions

MobyLives

NewPages Weblog

Omnivoracious

Page-Turner

PowellsBooks.Blog

Three Percent

Typographical Era

Moleskine

Papeles perdidos

Perlentaucher

Rép. des livres

Arts & Letters Daily

Arts Beat/Books

Bookdwarf

Brandywine Books

Buzzwords

Collected Miscellany

Light Reading

The Millions

The Page

ReadySteady Blog

The Rumpus

Two Words

Waggish

wood s lot

See also: links page

saloon statistics

opinionated commentary on literary matters - from the complete review

The

Literary Saloon

Archive

21 - 28 February 2014

21 February: Shugaar on translation | The value of a good translator | Diagram Prize finalists | Severina review

22 February: Leonardo Padura Q & As | Literature and ethics | Preparing for the Best Translated Book Award longlist | Translation is a Love Affair review

23 February: Yu Hua Q & A | 'The Daphne' shortlists

24 February: New writing in ... Hindi | Etisalat Prize for Literature

25 February: Irrawaddy Literary Festival reports | The VIDA Count 2013 | The Deliverance of Evil review

26 February: OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature finalists | Wellcome Book Prize shortlist | Writing in ... Australia

27 February: New issue of World Literature Today | 'Atwood in Translationland' audio | The No Variations review

28 February: Jewish Quarterly-Wingate Prize | Ghana Literary Prize (ambitions) | Festival Neue Literatur

go to weblog

return to main archive

Jewish Quarterly-Wingate Prize | Ghana Literary Prize (ambitions)

Festival Neue Literatur

Jewish Quarterly-Wingate Prize

They've announced the winner of the Jewish Quarterly-Wingate Prize (though not yet at the official site, last I checked ...), with Landscapes of the Metropolis of Death by Otto Dov Kulka taking the prize; see Jon Stock's report, Otto Dov Kulka wins Jewish Quarterly-Wingate Prize 2014, as well as Ian Thomson's profile of Otto Dov Kulka: The most powerful writer on Auschwitz since Primo Levi, both in The Telegraph.

It's not under review at the complete review (and probably won't be), but see the publicity pages from Harvard University Press and Allen Lane (yes, this is yet another title published by a university press in the US and a 'commercial' publisher in the UK ...), or get your copy at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Ghana Literary Prize (ambitions)

The Ghana Literary Prize Foundation site seems to have been up for a couple of years already, but the prize itself still seems to be a work-in-progress -- so it's good to learn more about it now at GhanaWeb, where (the organization's chief communication officer) Louisa Buah talks about 'Ghana Literary prize'.

She suggests:The decline in reading culture in Ghana society is alarming so the ultimate goal of Ghana Literary prize is aimed at promoting creative writing and reading culture in the Ghanaian society which is very low at the current decade.They may be expecting a bit much -- "The prize will curb mental laziness" -- but at least they're ambitious.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Festival Neue Literatur

The Festival Neue Literatur -- "New Writing from Austria, Germany, Switzerland, and the U.S." -- runs today through Sunday in New York, and should be fairly interesting; watch curator Tess Lewis' video welcome and overview here.

Only one of the participating author's books is under review at the complete review -- Abbas Khider's The Village Indian.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

New issue of World Literature Today | 'Atwood in Translationland' audio

The No Variations review

New issue of World Literature Today

The March/April issue of World Literature Today is now available, with much of the material available online. Among the areas of focus: 2013 Puterbaugh Fellow Maaza Mengiste and 'Cross-Cultural Humor'.

Most important, all the reviews are available, in the World Literature in Review section.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

'Atwood in Translationland' audio

Margaret Atwood's recent 2014 Sebald Lecture, 'Atwood in Translationland' can now be heard in full online, here. (Presumably the video will also soon be available; I'll let you know.)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

The No Variations review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Luis Chitarroni's Diary of an Unfinished Novel, The No Variations, published by Dalkey Archive Press (and a nicely typical 'Dalkey'-title -- though I wonder how much confusion the nearly simultaneous publication of A.G.Porta's The No World Concerto caused ...).

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature finalists

Wellcome Book Prize shortlist | Writing in ... Australia

OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature finalists

They've announced the finalists for the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature in its three categories -- fiction, non, and poetry -- with the category-winners to be announced 30 March and the ($10,000) prize winner announced 26 April.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Wellcome Book Prize shortlist

They've announced the shortlist for the (£30,000) Wellcome Book Prize, awarded: "to the best book of fiction or non-fiction from 2013 which leads on a medical theme".

None of these are under review at the complete review, I'm afraid.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Writing in ... Australia

At The Guardian's Australia Culture Blog Brigid Delaney considers: Is this a golden age for Australian debut novelists ?

The focus on a quick break-through -- a first book that makes a splash -- is a bit troubling, but at least it's a start.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Irrawaddy Literary Festival reports | The VIDA Count 2013

The Deliverance of Evil review

Irrawaddy Literary Festival reports

The Irrawaddy Literary Festival was held recently, and there are now some more reports on it, including Douglas Long on Late for Nowhere: The downs and ups of the Irrawaddy Literary Festival.

One good point he makes is:One of the main draws at the festival -- and for many, the only draw -- was the appearance of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi on February 15.A larger-than-life figure, it's hard not to take advantage of her willingness to participate -- but a more focused literary focus would be nice, too. As Long suggests in closing:

I had mixed feelings about her inclusion in the event: Sure, she's swell and all, and of course her presence was an enticement to foreign authors who attended.

But it seemed unfair that only one Myanmar parliamentarian among many should be invited to the festival. Also, 10 other literary panel discussions -- which, ostensibly, were what the festival was all about -- could have been held in the time slots taken up by Daw Suu Kyi's two appearances.In the future, the Irrawaddy Literary Festival would do well to pour all of its resources into accommodating this kind of cultural exchange -- in particular, giving authors who are little-known to the international community a rare chance to shine -- rather than providing space to celebrity politicians who have plenty of other platforms from which they can speak.Meanwhile, in Eleven they report that Indigenous literature coming of age in Burma.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

The VIDA Count 2013

The VIDA Count 2013 -- where they: "manually, painstakingly tally the gender disparity in major literary publications and book reviews" -- is now out. They look at the number of book reviews that are written by women/men, the sex of authors of those reviewed books, and other applicable indicators (bylines, for example) -- and the picture often isn't pretty.

Faring as consistently poorly as ever are leading periodicals such as The New York Review of Books, the Times Literary Supplement, the London Review of Books, and The New Republic. Among the arguments they have explaining the disparity -- at least regarding the authors of books reviewed being predominantly male -- is that more books are published by men; see, for example, Ruth Franklin's A Literary Glass Ceiling ? from two years ago. This is certainly (and disappointingly) an issue with regards to books-in-translation (see my discussion of this from last year).

(As I note each year, the complete review remains shamefully, overwhelmingly sexist: in 2013 84.88% of the 205 titles reviewed were authored by men. I like to think that the remarkable consistency in the ridiculously low percentage of female-authored titles getting reviewed (I've been aware of and wondering about it for well over a decade) suggests a 'natural' sort of level, determined by the types of books (mainly in translation; scholarly books in a limited number of fields, etc.) I cover. But I'm probably deluding myself. Still, just as I consciously would never read a book 'just' because it is written by a man, I can't bring myself to read books 'just' because they're by women, to improve the statistics. [I do note that a quick, rough check of the books I've received as review copies so far in 2014 -- of which only about 20% were explicitly requested by me -- the percentage written by men appears to be over 90%.].)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

The Deliverance of Evil review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Roberto Costantini's thriller, The Deliverance of Evil, now out in the US as well.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

New writing in ... Hindi | Etisalat Prize for Literature

New writing in ... Hindi

In the Hindustan Times Manoj Sharma reports that Young turks re-inventing Hindi literature (and, yes, I'm as disappointed as you are that they're young turks, not young Turks).

So, for example:[Divya Prakash Dubey] belongs to a new line of authors in Hindi who are rewriting the rules of the game. Their aim is to take their books to a whole new generation of Hindi readers. Dubey aspires to be a Chetan Bhagat of Indian writing in Hindi as far as accessibility and entertainment value of his books are concerned.I am not sure this is an aspiration to be applauded (several of Bhagat's titles are under review at the complete review; see, for example, One night @ the call center), but fresh blood -- in the sense also of fresh forms of/approaches to fiction -- is probably a good thing, overall.

Dubey argues:The reason why Hindi does not have new, popular bestsellers like those in English, is because most of those writing in Hindi are stuck in a time warp, telling stories that aspirational youth of today cannot relate to.I worry a bit about literature that tries too hard (or at all ...) to 'relate' to any-one/thing, but you can see his point.

Interesting, too, that the market remains small:But unlike the Chetan Bhagats of the English world, there is not much money for these new-age Hindi writers. Most of their titles sell somewhere between 1,000-5,000 copies with each book priced at a modest ₹100-150.(Recall that Wikipedia puts the number of native speakers of Hindi at ca. 311 million (2010), fourth among all languages worldwide (and not far behind English).)

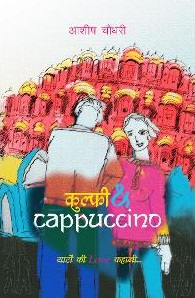

And I'm not sure how to react to, for example:"I am very particular that all the books that we publish have smart, youthful look, and interesting titles. Our upcoming Hindi novel is Kulfi And Cappuccino -- a love story set in Jaipur," says Bharatwasi.Kulfi and Cappuccino ? Yes, I groaned.

But as कुल्फी & Cappuccino (by Ashish Chaudhary) and with this cover:

Okay, pretty clever marketing.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Etisalat Prize for Literature

They've announced -- at least via 'tweet', if not yet at the official site, last I checked -- that We Need New Names by NoViolet Bulawayo has been awarded the inaugural Etisalat Prize for Literature -- a prize for: "writers of African citizenship whose first fiction book (over 30,000 words) was published in the last twenty four (24) months".

(Less prominently noted is the fact that only books first published in English are eligible, excluding an enormous amount of African literature: they actually fail to even mention (admit ?) that under their 'Criteria for Entry' on this page, only mentioning even farther down that "Entries fulfilling the criteria listed below will be accepted until the 30th August 2013", among which is: "the book was first published in English".)

I haven't seen We Need New Names -- which has been doing very well on the awards-circuit, with various long-and short-listings -- but get your copy at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Yu Hua Q & A | 'The Daphne' shortlists

Yu Hua Q & A

At ChinaFile Zhang Xiaoran has a Q & A with Yu Hua, Stranger Than Fiction.

He notes:I may write surrealist and absurdist novels, but that's because of the increasingly pervasive absurdity of Chinese society. But I'm still a realist writer.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

'The Daphne' shortlists

Bookslut has started the Daphne Awards, seeking to honor the best books of the year -- from fifty years ago -- in four categories (fiction, non, poetry and kid's stuff), and they've now announced the shortlists for the first go-round.

Counting 1963 as the year of first publication (rather than the year when the books originally appeared in English), the fiction list is a pretty impressive and translation-heavy one (and I'm a bit surprised to note that I've read all of them). Two of the books are even under review at the complete review: the obvious winner, Julio Cortázar's Hopscotch (the other titles are very good, but this is the towering -- and most influential -- work of fiction that saw the light of 1963-day) and The Ice Palace by Tarjei Vesaas -- and I do have a soft spot for two of the others: The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea by Yukio Mishima as well as The Grifters by Jim Thompson. (Meanwhile, it's good to see that some good sense and taste prevailed, and Mary McCarthy's The Group did not make the cut (as originally feared).)

I've even read some of the titles shortlisted in the other categories -- from Encyclopedia Brown to Hannah Arendt -- but find it hard to work up much interest in what's best of those lots.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Leonardo Padura Q & As | Literature and ethics

Preparing for the Best Translated Book Award longlist

Translation is a Love Affair review

Leonardo Padura Q & As

At Words without Borders' Dispatches weblog Nathalie Handal has a Q & A, The City and the Writer: In Havana with Leonardo Padura, and he's also featured in this week's Financial Times 'Small Talk'-column.

Quite a few Padura titles are under review at the complete review (see, for example, Havana Blue, or Adiós Hemingway), but I haven't seen his latest yet, The Man Who Loved Dogs (which I'm very much looking forward to). See also the publicity pages at Bitter Lemon Press and Farrar, Straus and Giroux, or get your copy at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Literature and ethics

At Stanford they have a Center for Ethics in Society, and there they recently held an event considering that age-old question, Does Reading Literature Make You More Moral ?. At the Stanford Report Justin Tackett now reports on the proceedings, in Stanford scholars debate the moral merits of reading fiction -- and if you're really curious you can watch the whole thing on YouTube.

This seems like kind of a tired old question to me, the simple answer of course being: No -- but, of course, there is a bit more to it than that, and credit them for at least exploring a couple of different aspects of the question.

(I suppose literature can help shape readers' morality by serving as a sort of thought-experiment, walking readers through moral dilemmas and suggesting what the various outcomes of various behavior might be; still, I'd be embarrassed if even the smallest bit of my moral compass was influenced by what I read. On the other hand, literature and its lessons seems a much better thing to use as a morality-guide than the one that's far more often used as an excuse, the recipe for so much disaster that is religion (fiction of the worst sort).)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Preparing for the Best Translated Book Award longlist

Like the other judges for the Best Translated Book Award, I am preparing to vote for the longlist (we begin voting 1 March; the longlist of twenty-five titles will be announced 11 March). We've been writing posts about the whole judging process for the past few months, and my final one, on trying to make those Final Selections, is now up at Three Percent.

I wrote the post more than a week ago, and by now more, rather than fewer titles, are in my mix as the day approaches -- and I'm still trying to get a few more books under my belt that look like they might be worth a closer look (two promising-sounding titles I hadn't previously seen arrived just yesterday ...). I don't have the proper distance yet -- and who knows what the actual longlist will turn out looking like (last year's top twenty-five only had seven of my top ten) -- but I don't think we've ever had this deep a field of good books, a few dozen worthies (along with a lot of crap, I hasten to add, with especially the mystery-titles a major disappointment this year). (I've actually been tempted to write a post on the worst of the books -- but leaving aside that that would be too unkind, there are just too many to choose from, too .....)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Translation is a Love Affair review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Jacques Poulin's nice little novel, Translation is a Love Affair, which Archipelago Books brought out back in 2009. (Yes, they sent me a review copy back then; yes, it's taken me until now to get to it, more than 1600 days later; that's just how things work (or don't) around here sometimes.)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Shugaar on translation | The value of a good translator

Diagram Prize finalists | Severina review

Shugaar on translation

At the Virginia Quarterly Review translator-from-the-Italian Antony Shugaar writes about Loss, Betrayal, and Inaccuracy: A Translator's Handbook.

Quite a few interesting observations -- though I wonder whether all translators agree with, for example:Another rule of translating the work of a living author is to keep the author out of the process until as late as possible.That an author likely wants to 'fix' "the English to look more like the original" is surely always an issue -- and maybe it's better to get an author's input right from the outset, to better understand what they were after in the original, no ? (Though of course resisting the 'fixes' that are offered and maintaining control over the translation is presumably a challenge every time.)

Well worth reading -- and see also another recent Shugaar piece, from The New York Times a couple of weeks ago, Translation as a Performing Art.

(Updated - 5 March): See now also Shugaar's response to this post.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

The value of a good translator

At PEN Atlas Otto de Kat writes 'about the risks and benefits of using history in the novel', in Imagining the past -- a few notes on the art of the historical novel.

That's reasonably interesting, but his piece also includes the best anecdote demonstrating the value of a good translator (and just how much that job involves) I've come across in a while:(I)n my last novel, News from Berlin, Emma Regendorf is arrested at her home by the Gestapo. They drive her to the Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse and they pass the Potsdamer Platz. Emma notices that the clock on the Platz is working as usual. And at that point I mention in the novel the peculiar form of the clock, namely its four sides, each with an individual clock-face. It is 1941, and the clock has always been a sort of landmark, placed there in the twenties. But what I didn't know was that it had been removed from the square in 1939 (and it was brought back after the war), so in 1941 there was no clock with four sides. My German translator, Andreas Ecke, the most dedicated and capable translator a writer can wish for, dryly informed me about that fact. He saved me from a few letters...That may be fairly common knowledge even in present-day Berlin, but it still seems like an awesome catch to me -- setting the bar pretty high for fellow-translators.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Diagram Prize finalists

The always popular Diagram Prize for Oddest Book Title of the Year has revealed its finalists.

I hope someone is doing a study to see the sales-effect shortlisting has on these titles.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Severina review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Rodrigo Rey Rosa's Severina, just out in Yale University Press' the Margellos World Republic of Letters series.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

previous entries (11 - 20 February 2014)

archive index

- return to top of the page -

© 2014 the complete review

Main | the New | the Best | the Rest | Review Index | Links