the

Literary Saloon

the literary

weblog

at the

complete review

the weblog

about the saloon

support the site

archive

Books, Inq.

BookRiot

Bookslut

Con/Reading

Critical Mass

GalleyCat

Guardian Books

Jacket Copy

The Millions

MobyLives

NewPages Weblog

Omnivoracious

Page-Turner

PowellsBooks.Blog

Three Percent

Typographical Era

Moleskine

Papeles perdidos

Perlentaucher

Rép. des livres

Arts & Letters Daily

Arts Beat/Books

Bookdwarf

Brandywine Books

Buzzwords

Collected Miscell.

Light Reading

The Millions

The Page

ReadySteady Blog

The Rumpus

Two Words

Waggish

wood s lot

See also: links page

saloon statistics

opinionated commentary on literary matters - from the complete review

The

Literary Saloon

Archive

11 - 20 February 2016

11 February: Íslensku bókmenntaverðlaunanna | Book reviews in ... German(y) | Natasha Wimmer Q & A | The Absolute at Large review

12 February: Bottom's Dream - the cover | Yomiuri Prize for Literature | Cairo International Book Fair report

13 February: Michael Wood on The Story of The Stone | Chad Post Q & A

14 February: Forthcoming in ... South Africa | Caterva review

15 February: Economics books (not) in French | Singaporean literature abroad | The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack review

16 February: Publishing in ... Russia | Emma Ramadan Q & A | Les inRocks: best books of past thirty years

17 February: New Directions profile | Introducing Raduan Nassar | Death of a Georgian translator | Depeche Mode review | Complete Review profile

18 February: 2015 Translation Prizes | Writing in ... Russia | Publishing in the ... United Arab Emirates

19 February: 2016 PEN World Voices Festival | Gran premio svizzero di letteratura | Erich-Maria-Remarque Peace Prize to Adonis | City of Love and Ashes review

20 February: Umberto Eco (1932-2016) | Cercas reviews

go to weblog

return to main archive

Umberto Eco (1932-2016) | Cercas reviews

Umberto Eco (1932-2016)

Italian author Umberto Eco -- best known for his novel, The Name of the Rose, has passed away; see, for example, Jonathan Kandell's Umberto Eco, 84, Best-Selling Academic Who Navigated Two Worlds, Dies in The New York Times.

(If for some reason you haven't read The Name of the Rose yet, you've missed something; get your copy at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk; there's also a nice Everyman's Library edition available.)

Worth revisiting also: Lila Azam Zanganeh's 'The Art of Fiction'-Q & A with Eco in The Paris Review (2008).

Only two of his titles are under review at the complete review (plus one review-overview): And I can't help but wonder/worry what happens to his wonderful, enormous library (but surely he made proper arrangements for it ...).

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Cercas reviews

The most recent additions to the complete review are my reviews of two early Javier Cercas novel(la)s -- published together in one slim volume in English as The Tenant and The Motive:

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

2016 PEN World Voices Festival | Gran premio svizzero di letteratura

Erich-Maria-Remarque Peace Prize to Adonis

City of Love and Ashes review

2016 PEN World Voices Festival

The 2016 PEN World Voices Festival will run in New York City 25 April through 1 May, and they have now posted the programme (and list of participants, etc.).

This year Mexico is highlighted -- and it all looks pretty promising.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Gran premio svizzero di letteratura

They've announced the Swiss Literary Prizes -- the multiple literary ones, awarded for individual works, as well as the Swiss Grand Prix of Literature (or, since it went to an Italian-writing author this year, the Gran premio svizzero di letteratura), won this year by Alberto Nessi.

Not an author who has made much of an English impression -- but see, for example, the brief Alberto Nessi: In search of mystery in Ticino at swissinfo.ch.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Erich-Maria-Remarque Peace Prize to Adonis

They announced quite a while ago that poet Adonis would be getting this year's Erich-Maria-Remarque-Friedenspreis, and it's been the source of much debate and discussion since.

Today, he finally gets to pick up the prize -- and at DeutscheWelle Kersten Knipp reports that Syrian poet Adonis hits back at criticism over German peace prize, as he faced the press yesterday.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

City of Love and Ashes review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Egyptian author Yusuf Idris' 1956 novel, City of Love and Ashes.

(I'm used to publishers sometimes getting summary- and information-copy (on covers, flaps, etc.) about their books and authors wrong, but the American University in Cairo Press' paperback sports one of the odder slips I've come across: the back flap author information says: "he continued to write and publish prolifically until his death in 1990", while the almost identical 'About the Author' information printed on one of the back pages concludes: "he continued to write and publish prolifically until his death in 1992". Which one is right ? Neither ! You have to split the difference: Idris passed away in 1991.)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

2015 Translation Prizes | Writing in ... Russia

Publishing in the ... United Arab Emirates

2015 Translation Prizes

Yesterday the Society of Authors announced the winners of this year's (six) Translation Prizes, for translations from the Arabic, Dutch, French, German, Spanish, and Swedish. (There are a varying number of prizes each year, since some of these are annual and others aren't .....)

(Good work with the announcement, by the way: while these are still among the most confusing prizes out there -- the umbrella-term 'Translation Prizes' suggests some uniform process (and prize-amount), but they pay out different amounts, all have different sponsors, and some (like the Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation), reveal the winner ahead of time -- but for many years the real annoyance was that we'd have to rely on the advert and then the summary-article appearing annually in the Times Literary Supplement to learn who won, with website-information added ... not in a timely manner. This year the Society of Authors did it right, posting this detailed press release -- with links to individual press releases for each of the prizes, too ! -- very quickly after the official ceremony/announcement. (Those of us who peeked into this week's TLS did learn the winners' names just ahead of time, but this openly accessible and thorough information is obviously the way to do things -- well done !))

Among the winners was serial-translation-prize-winner The End of Days, Susan Bernofsky's translation of Jenny Erpenbeck's novel, while the only winning title that is under review at the complete review is Outlaws (Anne McLean's translation of Javier Cercas' novel). (Several of the commended novels are under review: The Giraffe's Neck by Judith Schalansky; Tristana by Benito Pérez Galdós (a title that was neither Best Translated Book Award eligible (re-translation), nor Independent Foreign Fiction Prize eligible (dead author)); and Arnon Grunberg's Tirza (a deserving title and translation (by Sam Garrett) which I was pleased/amused to see still be in the running for a prize, quite a while after it came out).

Not much guidance here for the upcoming big translation-prizes on both sides of the Atlantic -- the new version of the Man Booker International Prize (which replaces the IFFP), and the Best Translated Book Award -- but it's time to start thinking about what those longlists will look like ..... I'm looking forward to much idle speculation .....

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Writing in ... Russia

At RBTH Yulia Vinogradova has a Q & A with Maya Kucherskaya, director of "the newly opened Creative Writing School" -- a unique ("there are no other schools of this kind in [Russia]" -- so Kucherskaya) -- institution (though I would have thought the good old Gorky Institute was exactly that kind of school).

Among her observations:The modern Russian prose market is incredibly small and niche. You can count the number of Russian publishers who work with contemporary authors on one hand. [...] Our market is so small that you simply don't need an agent to navigate it. An upside of how hard it is to be an author in Russia is that it filters out casual, redundant writers. Only people who truly have writing in their blood try their hand at literary work.(She really believes that ? Just think how many self- (and 'professionally'-)published hacks -- all with 'writing in their blood', all earnestly dedicated to their craft, but without any talent -- continue to churn out huge numbers of books in the US and elsewhere.)

And:The appeal of Russian literature in other countries is highly dependent on the political situation. The sanctions and wars have made people tired of Russia, and it is simply too much for most of them to separate the country's political image from its literature, to figure out that politics and literature are separate entities.(Again: really ? This is not my impression at all. Though admittedly US/UK publishers do seem to favor the bleak tomes of Russian-life-today (or also in the (Soviet) past) over fiction that is disengaged from the contemporary (or recent) political scene(s).)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Publishing in the ... United Arab Emirates

In UAE they tackle this problem like almost all the others: not enough books being published locally ? throw money at the problem ! So, as Thaer Zriqat reports in The National, Sharjah hopes to publish 1,001 Emirati books by 2017 -- and how ? with a: "Dh5 million campaign, titled '1001 Titles'".

Yes, this will: "encourage Emirati writers and publishing houses to print and publish 1,001 new books by 2017" -- though: "The KWB will fund the new titles depending on the type and quality" (i.e. presumably not all with qualify), and even if all DH5 million goes to books ... well that's a bit more than US$1300 per title, which seems like fairly little encouragement .....

Still, even if wildly overambitious, anything that prods the local market and gets some money into the hands of writers and publishers should at least help a bit.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

New Directions profile | Introducing Raduan Nassar

Death of a Georgian translator | Depeche Mode review

Complete Review profile

New Directions profile

At The New Yorker's Currency-weblog Maria Bustillos profiles the publisher, explaining: How Staying Small Helps New Directions Publish Great Books.

New Directions, founded in 1936, continues to have "a staggering list" of authors, with fiction in translation one of their greatest strengths. (Bustillos focuses on the great recent discovery, Eka Kurniawan's Beauty is a Wound, but that's just one of quite a few recent highlights.)

Interesting to hear about some of the terms of founder James Laughlin's will, limiting both the number of employees (nine), and the number of titles published annually -- with publisher Barbara Epler noting:The trust is just how he left it to make it safe, so we couldn't be bought by a larger corporation.An unusual publishing industry poison-pill arrangement -- neat ! (And good to see that it's worked as planned.)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Introducing Raduan Nassar

In The Independent Stefan Tobler explains that Raduan Nassar became a Brazilian sensation with his first novel -- now published in English, the world will come knocking, as two of his works are coming out -- apparently only in the UK (not yet the US), for now -- as Penguin Classics: A Cup of Rage (get your copy at Amazon.co.uk) and Ancient Tillage (get your copy at Amazon.co.uk).

It's a good introduction to an interesting writer, belatedly being introduced to English-speaking audiences -- but Tobler (and the headline writer) skirt a bit around the issue: "now published in English, the world will come knocking" ? really ? given that A Cup of Rage appeared in French in 1985 and in German in 1991 I think 'the world' (outside the US/UK) is, as is so often the case, a couple of steps (or miles ...) ahead .....

(Beyond the silly headline, Tobler fudges a bit too, admitting: "French, German and Italian editions already exist" but without indicating that they're not recent ones -- right after claiming: "over the years, the author has resisted translations of his works" (which, at least to me, implies the translations are all recent phenomena -- which of course they're not).)

I suppose it makes a better story to herald the English translations as discovering-him-for-the-world -- and certainly it should give him a nice boost in many markets, worldwide --, but let's be clear: significant parts of the the rest of the world were already well aware quite some time ago.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Death of a Georgian translator

As Agenda.ge report, Bachana Bregvadze, translator of world literature into Georgian, dies.

He showed an impressive range -- "He translated literature into Georgian from Ancient Greek, Latin, Italian, French, Spanish, German, Portuguese and Russian" -- and seems to have had quite the reputation:During his lifetime Bregvadze was awarded almost all of the most prestigious Georgian literature prizes and had two Medals of Honour.Both the Georgian president and the prime minister are quoted in the article -- that's pretty high-profile for a translator.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Depeche Mode review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Serhiy Zhadan's novel of early post-Soviet Ukraine, Depeche Mode.

This was the first of Zhadan's novels to be translated into English (to far too little notice ...), but two more are due out soon: Voroshilovgrad, forthcoming from Deep Vellum (see their publicity page, or pre-order your copy at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk) and Mesopotamia, coming out in Yale University Press' great Margellos World Republic of Letters-series (no publicity or pre-order page, but see the (English) Suhrkamp foreign rights page). It's about time -- along with Yuri Andrukhovych (Perverzion, etc.) and Oksana Zabuzhko (Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex, etc.) he is one of the leading contemporary Ukrainian authors.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Complete Review profile

At The New Yorker's Page-Turner weblog Karan Mahajan (Family Planning, and the forthcoming The Association of Small Bombs) writes about: One Man's Impossible Quest to Read -- and Review -- the World.

Hey, that's me !

It reminds me that I've been remiss in posting State-of-the-Site surveys the past two year (though there has been more number-crunching at this Literary Saloon to make up for some of that) -- and, for much longer, in making the site a bit more up-to-date (at least in appearance). But, yes, the focus is and remains almost entirely on content over form/appearance -- steady literary- and review-coverage, the flow of which continues steadily and unabated.

And, yes, there's The Complete Review Guide to Contemporary World Fiction to look forward to, forthcoming from Columbia University Press almost exactly two months from now; see their publicity page, or pre-order your copy at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk; see also, for example, early reviews at Goodreads.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Publishing in ... Russia | Emma Ramadan Q & A

Les inRocks: best books of past thirty years

Publishing in ... Russia

At The Intercept_ Masha Gessen reports that 'Putin Doesn't Need to Censor Books. Publishers Do It for Him', in Russian Purge.

Apparently, in a shift from the Soviet era:The fear of the censor has been replaced, to a great extent, by the fear of losing money. If a publishing house puts out a book that stores will not sell, it will face losses.Among the problems:The Russian reading public's tastes have distinctly narrowed in the last few years: All the publishers I interviewed for this series mention that readers increasingly reject serious topics, be they politics or, say, cancer, in favor of escapist entertainment(Though isn't this a complaint we hear about very many markets ?)

And:Book publishing is dominated by two large publishing houses and a handful of bookstore chains, which are private but take pains not to run afoul of the state. Smaller publishers take bigger risks, but the big booksellers reject their wares, marginalizing them further.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Emma Ramadan Q & A

At the Asymptote blog Megan Bradshaw has a Q & A with Emma Ramadan about her translation of Anne Garréta's fascinating Sphinx -- lots of interesting detail, about a translation that should be an early Best Translated Book Award favorite.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Les inRocks: best books of past thirty years

French magazine Les Inrockuptibles is celebrating its thirtieth anniversary, and so they're looking back over the past three decades -- including suggesting 30 ans des Inrocks: nos meilleurs livres sortis depuis 1986, where they have several contributors suggest their top tens.

Always interesting to see what publications in other countries consider the best-of, but particularly striking for this publication is that of the many books in translation that make the cut, practically all were translated from the English; as best I can tell, Murakami's Kafka on the Shore is the very lone exception. More a reflection of their editorial line than anything else, I assume -- but still: poor show.

The most-named French authors on the lists are Modiano and Houellebecq, with three mentions apiece -- though interestingly, there was no Modiano-consensus: they name three different titles.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Economics books (not) in French | Singaporean literature abroad

The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack review

Economics books (not) in French

In Le Temps Emmanuel Garessus considers why so few foreign (especially and/or even English-language ones) economics and business titles are translated into French, in Un livre éco, quelle horreur !

He gives six main reasons, ranging from the fact that 'France privileges novels' (as well it -- and everyone -- should !) to the fact that many of the interested readers can read the works (at least if they're in English) in the original. Good to see some self-awareness about the (delusions of) "un sentiment de la supériorité du modèle économique français", too.

(Of course, the most successful translated work about economics of recent years was actually translated from the French into English -- Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century (see the Harvard University Press publicity page, or get your copy at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk).)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Singaporean literature abroad

In the Straits Times Yuen Sin reports on Who's afraid of 'chao ah beng' ? Overseas universities use Singaporean literature to teach, as:At least 10 universities have introduced Singaporean texts in recent years, often in global literature courses.Good to see some foreign interest/attention (even if it is mainly academic ?) -- but disappointing that, as Singapore Literature Festival-organizer Koh Jee Leong notes:I think it's a shame that Singaporean literature is increasingly being read, even studied, abroad, but that Singaporeans themselves have been so reluctant to embrace our own writers.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of the first in Mark Hodder's six-volume steampunk series featuring the odd but hard to resist pairing of Richard Francis Burton and Algernon Charles Swinburne, The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Forthcoming in ... South Africa | Caterva review

Forthcoming in ... South Africa

At Books LIVE Jennifer runs down The local fiction to look forward to in 2016 (Jan - June) in South Africa.

Always interesting to see what gets published in other countries -- especially a place like South Africa, where even though the majority is written in English, very little finds its way to the US/UK markets.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Caterva review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Juan Filloy's 1937 novel, Caterva, recently published in English by Dalkey Archive Press.

Filloy -- who died aged over 100 -- is a fascinating figure, and among the titbits from translator Brendan Riley's Introduction: since his death three books have been posthumously published -- but there are still twenty-one unpublished ones ! (As far as English, the situation is even worse, with this just the second work available in translation (while Faction has been long-announced but oft-delayed ...).)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Michael Wood on The Story of The Stone | Chad Post Q & A

Michael Wood on The Story of The Stone

In The Guardian Michael Wood wonders Why is China’s greatest novel virtually unknown in the west ? -- meaning, of course, Cao Xueqin's The Story of The Stone (also known as Dream of the Red Chamber), which I hope many of my readers are, in fact, familiar with.

Wood apparently shared a house with translator David Hawkes while at Oxford, so there's some nice background about him and the translation, too.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Chad Post Q & A

At Book Riot Rachel Cordasco was Talking Translation With Chad Post of Open Letter Books, covering a variety of the-state-of-publishing-translations stuff.

(And always nice to see a The Weather Fifteen Years Ago shout-out !)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Bottom's Dream - the cover | Yomiuri Prize for Literature

Cairo International Book Fair report

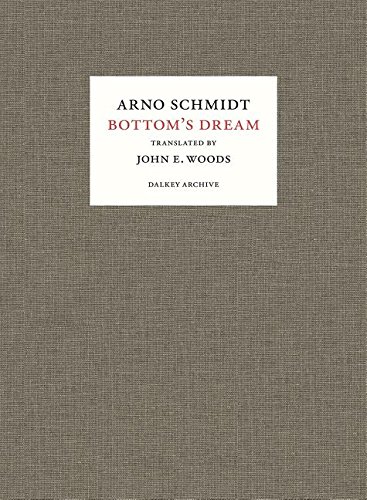

Bottom's Dream - the cover

So at the Amazon.com page (and Amazon.co.uk, etc.) they now have a cover up for the forthcoming-from-Dalkey Archive Press John E. Woods translation of Arno Schmidt's long- and much-anticipated (and long, and weighty) Bottom's Dream:

Hurrah ! (Also because this is yet another indication that the book will actually appear ... until I see it, I will harbor some doubts .....)

Stark and simple, like most of the German covers -- but good to see John E. Woods' name and role prominently featured.

Still a few months until it is (supposed to be) out -- but meanwhile remember: The School for Atheists is a great starter-Schmidt/preparation volume -- and, of course, for more Schmidt background, there's always my Arno Schmidt: a centennial colloquy (get your copy at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk).

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Yomiuri Prize for Literature

They recently announced the 67th 読売文学賞, with Furukawa Hideo's 女たち三百人の裏切りの書 taking the fiction prize.

Furukawa is definitely someone to look out for: Haikasoru brought out his Belka, Why Don't You Bark ? a few years ago (see their publicity page, or get your copy at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk), while Columbia University Press is bringing out his Horses, Horses, in the End the Light Remains Pure shortly (see their publicity page, or get your copy at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk). (I have both, and should be getting around to reviewing them.)

See also the (Japanese) Shinchosha publicity page for the prize-winning title, or the (English) J'Lit Hideo Furukawa page, which also has information about some of his other not-yet-translated titles.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Cairo International Book Fair report

In Al-Ahram Weekly Nevine El-Aref reports on the recent Cairo International Book Fair, in Of books and bread.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Íslensku bókmenntaverðlaunanna | Book reviews in ... German(y)

Natasha Wimmer Q & A | The Absolute at Large review

Íslensku bókmenntaverðlaunanna

As Vala Hafstad reports at Icelandic Review, Icelandic Literature Prizes Presented, as the country's major literary awards have been handed out, with Hundadagar, by Einar Már Guðmundsson (several of whose works have been translated into English) taking the fiction prize -- beating out, among other finalists, Hallgrímur Helgason and Jón Kalman Stefánsson. See also the Forlagið publicity page for the book.

The prize is worth an impressive(-sounding) ISK 1 million -- though apparently that's now only the equivalent of ca. US$7,800.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Book reviews in ... German(y)

At the German Perlentaucher site they've long been collecting book review coverage from the major German-language dailies of books appearing in German(y), and Thierry Chervel now looks over the numbers and some other analyses in Kritische Zahlen, to see whether --or rather just how much -- book review coverage in German newspapers (plus the Swiss NZZ) has declined since 2001.

Short -- and disturbing -- answer: a lot.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Natasha Wimmer Q & A

Alicia Kennedy has a(n awfully-titled) Q & A with translator Natasha Wimmer at Broadly.

(I just picked up a copy of the Wimmer-translated Enrigue, Sudden Death, at the library, and look forward to getting to it soon. (Get your copy at Amazon.com or pre-order it at Amazon.co.uk.))

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

The Absolute at Large review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Karel Čapek's 1922 The Absolute at Large.

I actually received my review copy of this book 3815 days before the review went up -- so, yes, sometimes it takes me a while .....

(This is actually the third from this University of Nebraska Press Bison Frontiers of Imagination-series that I had previously read (all in German, all decades ago) and eventually got around to re-reading and then reviewing, in each case 2000 or more days after getting the UNP edition of the book. I guess they just have to be lying around long enough until I finally can't resist any longer .....)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

previous entries (1 - 10 February 2016)

archive index

- return to top of the page -

© 2016 the complete review

Main | the New | the Best | the Rest | Review Index | Links