the

Literary Saloon

the literary

weblog

at the

complete review

the weblog

about the saloon

support the site

archive

Arts Journal

Books, Inq.

BookRiot

Bookslut

BritLitBlogs

Con/Reading

Critical Mass

GalleyCat

Guardian Unlimited

Jacket Copy

The Millions

MobyLives

NewPages Weblog

Omnivoracious

Page-Turner

PowellsBooks.Blog

Three Percent

Typographical Era

Moleskine

Papeles perdidos

Perlentaucher

Rép. des livres

Arts & Letters Daily

Arts Beat/Books

Bookdwarf

Brandywine Books

Buzzwords

Collected Miscellany

Light Reading

The Millions

The Page

ReadySteady Blog

The Rumpus

Two Words

Waggish

wood s lot

See also: links page

saloon statistics

opinionated commentary on literary matters - from the complete review

The

Literary Saloon

Archive

1 - 10 December 2013

1 December: Favourite Scottish novel (of past 50 years) | Translating from ... Tamil | No One Writes Back review

2 December: December issues | André Schiffrin (1935-2013) | Literature in ... Viet Nam | Perumal Murugan profile

3 December: Publisher profiles: And Other Stories - Text Publishing | Writing in ... Cambodia | Geoffrey Hill Oxford lecture

4 December: Bestselling in ... Japan | Korean literature abroad | Vietnamese literature in ... France | Literary Review Bad Sex in Fiction Award | The Restoration Game review

5 December: Prizes: Русский Букер - Franz Nabl-Preis | The Faint-hearted Bolshevik review

6 December: Daniel Mendelsohn Q & A | French literary prize statistics | Popescu Prize | Wole Soyinka Q & A

7 December: Munro's Nobel lecture | Prizes: European Book Prizes - Crossword Book Awards | Night Train to Lisbon - the film | Zibaldone coverage

8 December: The complete Trial | A Wild Sheep Chase in ... Iran | Book prize judging

9 December: Finlandia Prize for Fiction | Korean writing in ... France | Philippine PEN center conference | Vernacular military literature in India ? | Happy Valley review

10 December: French fiction abroad | 'International bill of digital rights' | Nobel sales bump | Helmerich Author Award | Zündel's Exit review

go to weblog

return to main archive

French fiction abroad | 'International bill of digital rights' | Nobel sales bump

Helmerich Author Award | Zündel's Exit review

French fiction abroad

At BBC News Hugh Schofield has an interesting piece with lots of quotes from prominent French authors wondering Why don't French books sell abroad ? -- specifically, in the English-speaking world.

The first point to make here is that, rights/title-wise, they do sell well. Translations-from-the-French routinely outnumber those from any other language into English by a large margin, and long have; the Three Percent Translation Database (covering all translated-for-the-first-time works of fiction and poetry published/distributed in the US) currently (the numbers aren't final) has 75 out of the total of 419 titles listed as being from the French, way ahead of the number two languages (a tie between German and Spanish, with 49 titles each). (Consider also: I am a judge for the Best Translated Book Award fiction prize, and while we're considering well over 50 French titles (the database counts both fiction and poetry ...), as best I can tell only three (!) works translated from the Chinese are eligible this year .....)

Nevertheless, authors whinge:"I am suffering, really suffering, because Anglo-Saxon agents are just ignoring the French book market," Christophe Ono-dit-Biot tells me.With all due sympathy -- hey, I'd love to see some of his books available in English -- I repeat: all of three works of fiction translated from the Chinese have been published in the US this year. So there's being ignored, and there's being ignored .....

The article is filled with priceless quotes by French authors -- a favorite being (I cruelly take it slightly out of context):"Personally I am fed up with all the stereotypes," says Darieussecq. "We're not intellectual.Whatever she says .....

It's not that they're entirely clueless; indeed, they have a semi-valid point. But even as the French fare relatively poorly, I remind you how much worse everyone else fares in translation. (Again: China -- three previously untranslated works of fiction published in the US this year .....)

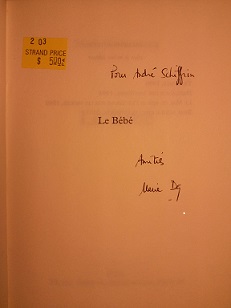

Indeed, Marie Darieussecq, for example, has done quite well -- and four of her works, all available in English (as is one more), are even under review at the complete review. Still, I can understand her frustration: her best-known work, Pig Tales, was published by André Schiffrin's The New Press -- and yet among the saddest purchases I ever made of a used book (it still breaks my heart every time I open it) is one with this title page:

Meanwhile, Marc Levy -- author of, for example, All Those Things We Never Said -- moans:If you've been a best-seller in France, it's a sure-fire recipe for not getting a deal in the UK.(Levy is a fascinating case study for trying to break into the English-language market, as he's recently tried to do through the publishing venture Versilio; scroll down for various of his titles in English (mostly just in ebook form ...).)

I recently joked/complained about US publisher Simon & Schuster touting the arguably under-translated Philippe Djian as "France's #1 Bestselling Author" (without any supporting evidence -- and there's none I can find), but even some of his books continue to dribble into English. (Admittedly relatively few, but still .....)

As far as real bestselling authors go: the list of top-selling French authors doesn't change too much from year to year, and Le Figaro's for 2011 will serve as good enough an example (it's available in English, so ...). Levy is on it (number two), and most of the other authors on it have also had at least one or two titles translated; aside from mystery writer Fred Vargas, and, arguably, Amélie Nothomb, most have not fared that well in the US/UK market. But I have to say, other than Nothomb -- who, as longtime readers know, I have a very soft spot for -- I have not been particularly impressed by any of the works by these authors appearing in translation (quite a few of which I've reviewed at the complete review): French bestselling crap-fiction isn't worse than American bestselling crap-fiction (which also leaves me cold), but you can see how it can be a harder sell here.

Meanwhile, Tatiana de Rosnay has taken to writing some of her fiction directly in English (Sarah's Key ...) -- while longtime New York resident (she lived here for a decade) Katherine Pancol -- third bestselling French author in France in 2011 -- is finally appearing in English with The Yellow Eyes of Crocodiles. I recently got my (English) copy of that -- Penguin Books is bringing it out, 31 December -- and Pancol's Acknowledgements cruelly note that it is already available in twenty-nine other languages ..... But what really kills me is the little note on the copyright page:This edition is an abridgement of the original French-language work.Edits in translation are, sadly, the norm, but when publishers own up and actually acknowledge them you know they've fucked the text over pretty bad -- as the much lower page-total here also suggests. I know nothing about how the publishing business 'works', as I often remind you -- but this certainly does not seem the route to any sort of success (and seems among the possible answers to 'Why don't French books sell abroad ?'). (A 31 December publication date also looks a hell of a lot like an attempt to bury the poor book.)

The BBC piece also notes some 'Exceptions to the rule', books that have sold well -- Atomised (US title: The Elementary Particles), HHhH, and Suite Française -- though of course the latter is contemporary only in terms of publication date. (Interestingly, HHhH was apparently also subject to significant editorial interference in translation -- but then I remain baffled by its success in any case.)

Certainly, French literature isn't enjoying glory days abroad, or at least in the US/UK -- but then few literatures are. It's a bit odd that there are few stand-out authors, but a hell of a lot get translated and they fill a variety of niches, from Oulipo to titillating self-absorbed autofictions to the playful intellectual novels of, say Jean Echenoz, Emmanuel Carrère, Jean-Philippe Toussaint, and Lydie Salvayre (all well-translated into English) to mystery/thriller authors including Tonino Benacquista and Jean-Claude Izzo (also all widely translated into English).

On the other hand, I do continue to be baffled why some books and authors don't do better -- such as, recently, Jean-Marie Blas de Roblès' Where Tigers are at Home.

Again, I don't understand how publishing 'works', but US/UK publishers certainly play the game strangely -- so now with a rare recent French-language success story, as Penguin Books recently acquired US rights to Joël Dicker's prize-winning bestseller The Truth About the Harry Quebert Affair; see, for example, the Publishers Weekly report -- for, so the publicity claim, the biggest amount they've ever spent. Tellingly, however, they bought the rights from UK publisher MacLehose, who cleverly tied up world English rights; the book has appeared in numerous translations, and yet again English-speaking readers are left until relatively late in the game to get their chance to see it. Of course, this French-language success is small comfort to the French themselves: Dicker is Swiss.

(Updated): See now also Electric Flesh-author Claro's commentary on the BBC piece, Pour un style accessible et pas obsédé par les mots (ou comment s'exporter); I look forward to more French authors weighing in.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

'International bill of digital rights'

A stunning list of authors on board with this: some 560 authors from 83 nations, in a petition published in 32 newspapers across the world: see it at, for example, The Guardian: International bill of digital rights.

Admirable -- spread the word.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Nobel sales bump

A nice little study with some (though too few ...) hard numbers, as BookNet Canada and Nielsen Book analyzed Canadian and international sales data for Alice Munro's titles before and after her Nobel win, in Alice Munro, At Home and Abroad: How the Nobel Prize in Literature Affects Book Sales (warning ! dreaded pdf format !). (For those satisfied with press release-summary, see theirs.)

Mostly they just deal with percentage changes -- which look impressive, but then you remember how low average sales are without Nobel-prodding ..... So, for example, comparing the pre-announcement-period to the announcement week:During that week, sales increased from 94 units to a height of 6,345 units for all of Munro's titles, a 6650% increaseGreat that the Nobel helped shift so many copies ... but 94 units of this prolific author's books in the entire week (when she was already getting more coverage -- there was a lot of Munro-Nobel buzz in the Canadian press leading up to the announcement) ... ? Sigh.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Helmerich Author Award

To my embarrassment, I was completely unfamiliar with the Peggy V. Helmerich Distinguished Author Award --:an annual award given by the Tulsa Library Trust. Its purpose is to give formal recognition, on behalf of the Tulsa County community, to internationally acclaimed authors who have written a distinguished body of work and made a major contribution to the field of literature and letters.It comes with a $40,000 cash prize and an engraved crystal book (huh ?), too -- and winners include Ian McEwan, Joyce Carol Oates, Margaret Atwood, Norman Mailer, Saul Bellow, Toni Morrison, and John Updike. I.e. pretty high-profile for an author prize.

Anyway, they handed out the 2013 award last week, to Never Let Me Go-author Kazuo Ishiguro; see, for example, David Harper's report, 2013 Helmerich Award winner Kazuo Ishiguro says songwriting came first in Tulsa World.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Zündel's Exit review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Markus Werner's 1984 novel, Zündel's Exit, now available in English from Dalkey Archive Press, in a translation by Michael Hofmann.

(I guess Werner is slowly catching on in the US/UK: NYRB Lit -- Haus recently brought out his On the Edge (see their publicity page) in the UK, while in the US New York Review Books has published it in their electronic imprint, NYRB Lit (see their publicity page).)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Finlandia Prize for Fiction | Korean writing in ... France

Philippine PEN center conference | Vernacular military literature in India ?

Happy Valley review

Finlandia Prize for Fiction

They've announced the winner of the Finlandia-palkinto, with Riikka Pelo taking the prize for her Marina Tsvetaeva-novel, Jokapäiväinen elämämme ('Our everyday life'); see also the Books from Finland report.

This is the leading Finnish literary prize -- with an impressive list of previous winners (several of which have been translated into English, most recently Sofi Oksanen's Purge and 2011 winner Rosa Liksom's Compartment No 6 due out next spring (pre-order your copy from Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk)) -- and I note that at €30,000 it pays out more than the Pulitzer, National Book Award, and National Book Critics Circles Award combined (twice over, even).

For more information about Jokapäiväinen elämämme , see the (Finnish) Teos publicity page, or the short (English) review at Books from Finland.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Korean writing in ... France

In The Korea Times Chung Ah-young reports that Korean author joins top French literary series, as some of Lee Seung-u's work -- quite a bit of which has been translated into French -- has now appeared in Gallimard's pocket-book Folio-series; she goes so far as to suggest:Lee's recent Folio edition proves that he is more widely recognized in France than in Korea.And she notes:Widely known for his interest in Korean literature, Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clezio, the 2008 Nobel Laureate for Literature, mentioned Lee Seung-u as a likely candidate for the prize, along with other Korean writers such as Anatoly A. Kim and Hwang Sok-yong.(Any Nobel-name-check list that includes Russian-writing Anatoly A. Kim -- pretty impressive. Note also that as a Nobel laureate Le Clézio is allowed to submit a nomination every year -- might he go the Korean route ?)

Lee Seung-u is, of course, not entirely unknown in English either -- indeed, The Reverse Side of Life is under review at the complete review.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Philippine PEN center conference

Last week they held the 56th National Conference of the Philippine Center of International PEN, and in the Philippine Daily Inquirer Amadís Ma. Guerrero offers an overview of the event, in War and peace -- and literature.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Vernacular military literature in India ?

Oridnarily I'm all for more writing and more publishing in local (and any) languages, in India and elsewhere, but I'm finding it hard to get on board here. As reported in the Times of India, 'No vernacular market for military literature', which sounds good to me -- but:Former Army chief, General Shankar Roy Chowdhary said we need more writers in vernacular language for military writingHmmmm .....

And:Maj Gen G D Bakshi conveyed "a need to eulogise modern military heroes to teach ethics and values to young growing children". He mooted the idea of Indian war comicsTeaching ethics and values, and eulogizing military actions appear to me to be entirely incompatible. And to combine 'war' and 'comics' -- to crudely simplify in drawings, and try to make palatable or even appealing the ugliest and most contemptible of human activities ... no, it's good to hear that writers, vernacular or otherwise, show little interest in having any part of this.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Happy Valley review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Nobel laureate Patrick White's first novel, Happy Valley.

Much of White's work has long been out of print (especially in the US), but this is a title whose unavailability White himself was long responsible for: he refused to allow it to be republished during his lifetime. Australian publisher Text have now finally brought the 1939 work out again, in their excellent Text Classics series -- and have now also brought it to the US, where some of the volumes from the series are being distributed.

(A warning, just in case you've not read any White before: despite the title, this is not a cheery work. Yet, despite being grim and grimmer, there's also a surprising verve to it -- so don't let that put you off it, either.)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

The complete Trial | A Wild Sheep Chase in ... Iran | Book prize judging

The complete Trial

The German Literatur Archiv Marbach is one of the more impressive literary museums, and most of their exhibits sound like they're worth a trip, but one of the new ones, Der ganze Prozess ('The whole trial') really stands out: they have (for the first time) the entire manuscript of Kafka's The Trial on display, along with diary and manuscript pages from related works (through 9 February).

In the Neue Zürcher Zeitung Andreas Breitenstein is the latest to rave about it, in Die Stunde der Papiere.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

A Wild Sheep Chase in ... Iran

Okay, they're not exactly up to date here -- Murakami Haruki's A Wild Sheep Chase came out in Japan in 1982 -- but, as IBNA reports, this novel has now also come out in Iran.

The cover is pretty cool, too:

It's always interesting to see what the hell they're publishing in Iran, and often surprising what does make it past the censors.

As it happens, this is also an interesting example of what happens in a (legal-)regime that's essentially a copyright free-for-all (since Iran isn't bound by the international rules on this (a two-way street, which also makes Iranian writings vulnerable to foreign (ab)use)). This novel may be some thirty years old, but it's apparently a hot title in Iran right now, as:The new book, translated by Mahmoud Moradi, is released while some two weeks ago another rendition, by Mahdi Qhabraie, had been marketed.Two different translations published in the space of two weeks !

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Book prize judging

In The New York Times Charles McGrath writes about his experiences as a judge for the fiction category of this year's (American) National Book Award, in Caution: Reading Can Be Hazardous.

He reveals that there were 407 entries (though he, and the NBF, and no one will tell you what they were, sigh ...), and he gives a nice overview of what it means to deal with so many books.

As a judge for the Best Translated Book Award, considering some 350 (give or take a few dozen) works of fiction, I can certainly commiserate -- especially with the where-to-put-all-those-damn-books problem ..... (On the other hand, not a single one of the ten longlisted NBA titles (warning ! dreaded pdf format !) has even come across my desk, so at least my piles remain dedicated entirely and solely to the task at hand.)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Munro's Nobel lecture | Prizes: European Book Prizes - Crossword Book Awards

Night Train to Lisbon - the film | Zibaldone coverage

Munro's Nobel lecture

It's Nobel ceremony time, and although literature laureate Alice Munro can't attend all the festivities, she videotaped a Nobel lecture which they will be screening at 17:30 CET today; see information here -- streaming, and a transcript, should be available around that time on the Nobel site.

(Updated - 8 December): You can now watch Munro's Nobel 'lecture', "Alice Munro: In her Own Words", or read the transcript.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Prize: European Book Prizes

The European Parilament press release reveals that they've announced the winners of this year's European Book Prizes (the best I can find at the official site isn't even the short list, but rather the preliminary présélection 2013 (which at least offers an interesting overview of recent European titles)).

Eduardo Mendoza -- author of The Mystery of the Enchanted Crypt and No Word From Gurb -- won the fiction category for another book that is already available in English, An Englishman in Madrid, published by MacLehose Press; see their publicity page, or get your copy at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk.

(There's also a non-fiction category; that prize went to Ces Français, fossoyeurs de l’euro, by Arnaud Leparmentier (which I mention only because, well, 'fossoyeurs' is a really cool word (and the fact that it means' 'grave-diggers' -- makes it even better. Those French !)).)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Prize: Crossword Book Awards

They've announced the winners of this year's Indian Crossword Book Awards (but, well, you know ... as my sadly tireless refrain has it: not at the official site, last I checked ...).

See, for example, the Times of India report for the winners -- of which there were two in the case of several categories. The translation prize went to M.Asaduddin's translation of Ismat Chughtai's A Life in Words -- good to see her work being honored, disappointing that it's not fiction but rather just her memoir; see also the Penguin India publicity page, or get your copy at Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, or Flipkart.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Night Train to Lisbon - the film

The film version of Pascal Mercier's Night Train to Lisbon, directed by Bille August and starring Jeremy Irons and Lena Olin -- see also the official site --, has now opened in the US.

Reviews suggest it's not really gripping -- review-headlines include: The Unfashionable Night Train to Lisbon Isn't Afraid of Being Dull (The Village Voice) and Night Train to Nowhere: Bille August’s Latest Is a Snoozer (The New York Observer) -- with Stephen Holden concluding his review in The New York Times: "After barely stirring to life, Night Train to Lisbon mercifully expires."

You can see how this intellectual thriller (emphasis way more on the intellectual ...) probably works better on the page than on the screen -- and it is a good novel, so don't let the film scare you off it.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Zibaldone coverage

It'll still be a while before this comes together as any sort of proper review, but preliminary coverage of the incredible new translation of Giacomo Leopardi's Zibaldone -- one of the publishing-events of the year -- is now up, with the hope that a proper review will slowly coalesce out of my reading. (Meanwhile, it at least serves as a useful page for links to all the other reviews, etc.)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Daniel Mendelsohn Q & A | French literary prize statistics

Popescu Prize | Wole Soyinka Q & A

Daniel Mendelsohn Q & A

At Prospect David Wolf continues his interesting 'Critical thinking'-series of Q & As 'about the art of criticism' -- this time with Daniel Mendelsohn.

As readers might recall, just three weeks ago I took issue, at some length, with Mendelsohn writing in a 'Bookends'-column in The New York Times Book Review about how vital he felt it was for the critic to consider any particular book very much in the context of the author's entire body of work (whereas my strong preference is to focus on the work at hand and ignore, as far as possible, the hand behind it).

He's at it here again:I still think it's imperative, even if you're a weekly critic, to do more than read the book in question. It's still inconceivable to me for anybody, including a newspaper critic with a weekly beat, not to read the other works by an author. It's just irresponsible not to do that because you're failing to do your job, which is to make things interesting and coherent for your reader. If you haven't read the author's other books, you don't know if the book that you're reviewing represents an evolution, an improvement or whatever.Quite honestly, I continue to be baffled by this. Yes, the literary biographer or historian, and arguably even some practitioners of literary criticism have some reason to go in for this sort of thing -- but not, I'd suggest, 'simple' book reviewers (i.e. those who write reviews for publications aimed at a more or less general audience -- from the complete review to The New York Review of Books).

I get that it's hard to look at the new (or old) Philip Roth without considering/seeing/being blinded by all the other Roths; hell, I've just read Patrick White's debut, Happy Valley (review to follow soon) and it was incredibly difficult not to constantly consider it in the larger White-context.

Nevertheless, I still maintain a book-by-book approach is, in almost all cases far more useful. And I regret that Wolf didn't force the issue a bit, as Mendelsohn gave him a nice opening, mentioning his The New York Review of Books-review (not freely accessible online) of The Kindly Ones by Jonathan Littell. Not much discussion there by Mendelsohn of Littell's first book, Bad Voltage, or how Littell had moved on (including to a whole new language !) with The Kindly Ones.

Maybe Bad Voltage is, for some reason, simply negligible and doesn't have to be counted or considered -- not-quite-juvenilia ? a young author trying to find his literary niche ? Who knows ? I don't, but then that's because I prefer considering the book under discussion on its own terms -- as, in the case of The Kindly Ones, Mendelsohn did too.

Any future literary historian/biographer/scholarly critic of Littell will surely also take Bad Voltage into account re. any reading of The Kindly Ones -- but I imagine there's other extraneous matter that must also be considered (and likely offers more useful insight). Littell's time in the Caucasus is perhaps the most obvious, in leaving its traces in the book -- though I, for one, would imagine his father Robert Littell's writing is more significant than, for example, his own Bad Voltage and I'm surprised there hasn't been more rooting around in that.

Reading the Patrick White has been instructive, in many ways. Here's an author whose work I am very familiar with -- practically all of it -- and one way of reading it would have been to just look for clues to his future work here. Maybe something for the biographer or literary historian, but not me ..... Indeed, if we're considering context, it seems more useful to look at Happy Valley as a product of its times, rather than a product specifically of his, the influences (both the who and the what) -- Joyce, Stein, even Dos Passos -- more intriguing than considering, for eample, how specifically White moved on from here in his later work.

(In his 'Bookends'-column Mendelsohn suggests Donna Tartt as an author whose evolution reviews should chronicle and consider (yawn) -- but surely there's an argument for seeing both The Secret History and The Goldfinch in the contexts of their time -- not with respect to what else she has written, but rather what others are writing, and specifically what the world at large at those times looks like (especially given the roughly decade-long intervals between books): it seems far more interesting (to me) to consider The Goldfinch, with its strange slice of New York -- a sort of timeless version of the city that's barely recognizable as any version of the actual one in its broad outlines and yet nails so many specifics well -- in this respect than considering, for example, how Tartt's use of young-kid-protagonists has (or rather: hasn't) evolved from book to book.)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

French literary prize statistics

Le Monde has a pretty fantastic French literary prize graphic, considering: Littérature: les éditeurs qui raflent tous les prix showing which publishers have won the big prizes over the course of the last 110 years.

Well worth bookmarking.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Popescu Prize

A few days ago they announced that Memorial, by Alice Oswald, has won this year's Poetry Society Corneliu M Popescu Prize 2013 for poetry translated from a European language into English. (The shortlist impressively included translations from the Albanian, Estonian, and Galician -- and French classics (Rimbaud, Mallarmé), too.)

At PEN Atlas David Wheatley, one of the judges, now writes about Poetry in translation -- The Popescu Prize 2013.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Wole Soyinka Q & A

In Vanguard Japhet Alakam presents a Q & A Wole Soyinka recently had with students at the Ake Art and Books Festival, Winning the Nobel didn't affect my writing.

Quite a variety of (not your usual) questions -- and he explains why he wears collarless shirts.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Prizes: Русский Букер - Franz Nabl-Preis

The Faint-hearted Bolshevik review

Prize: Русский Букер

They've announced that Andrei Volos has won the 2013 'Russian Booker' (Русский Букер -- yes, despite no Booker cash, they inexplicably still retain the name ...) for his Возвращение в Панджруд; see also, for example, the elkost literary agency information page (yup, this one has gotten a lot of award-consideration -- enough to whet any US/UK publisher interest ?). See also the report at Lizok's Bookshelf.

He gets a decent prize-sum of about $45,000 -- but it's fellow finalist Маргарита Хемлин who cashes in with half that sum but also a translation-into-English deal, for Дознаватель.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Prize: Franz Nabl-Preis

The latest winner of the biennial €14,500 Franz Nabl-Preis -- the Literaturpreis der Stadt Graz ('literary prize of the city of Graz' -- Austria's second biggest city, and my hometown), an author (as opposed to book) prize (the Austrians, like the Germans, prefer doing the author- rather than book-honors) -- has been announced, and it is Slovenian-writing (a first !) Florjan Lipuš.

How serious to take the prize ? Well, they gave it to two Nobel laureates, pre-Stockholm -- Elias Canetti (1975) and Herta Müller (1997) -- and other prize winners include ... oh, just: Peter Handke, Christa Wolf, Martin Walser -- and, in more recent years, quite a few authors also available in translation (Terézia Mora, Josef Winkler, Urs Widmer, etc.). Not bad.

Good timing, too, because while you probably haven't gotten to Lipuš yet (at least in English) ... why, look here, Dalkey Archive Press have conveniently just come out with a translation (forty years after the fact and initial publication, but hey ...) of his The Errors of Young Tjaž -- a novel Peter Handke himself translated into German (which is a pretty decent seal of approval for a text). See their publicity page, or get your copy -- go on ! -- at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

The Faint-hearted Bolshevik review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Lorenzo Silva's The Faint-hearted Bolshevik, a 1997 Premio Nadal finalist that is now finally available in English, co-translated by Nick Caistor, and published by Hispabooks.

Hispa who ? Hispabooks, yet another model for fiction-in-translation-publishing. Spain-based, they're taking advantage of the new technologies -- my copy is basically a print-on-demand-one, spit out and delivered by Lightning Source (as a surprising number of the books I receive nowadays are), but looking every bit as good as any other trade paperback -- and introducing an impressive selection of Spanish titles to English-reading audiences.

It's amazing that this is the first Silva to make it into English -- after all, this guy has a decent track record, culminating in his taking the 2012 Premio Planeta -- a book prize whose €601,000 pay-out puts all English-language book prizes to shame.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Bestselling in ... Japan | Korean literature abroad

Vietnamese literature in ... France | Literary Review Bad Sex in Fiction Award

The Restoration Game review

Bestselling in ... Japan

In Japan they apparently operate on a slightly different calendar in calculating annual bestsellers, the most popular tallies now reporting the bestselling books of 2013 (which are, in fact, the bestselling books of 19 November 2012 to 17 November 2013 ...) ... and, as Ida Torres reports at JDP, Haruki Murakami's new novel tops Japan's 2013 best-sellers list, with 色彩を持たない多崎つくると、彼の巡礼の年 shifting some 985,000 copies, and putting it ahead of 医者に殺されない47の心得, which sold around 814,000 copies (but note that the Tohan bestseller lists (warning ! dreaded pdf format !) -- which actually list the books, but without sales-totals -- reverses the order, putting the Murakami second ...).

The Murakami is due out in English in 2014; I suspect it won't sell quite as many copies, even in the US/UK combined .....

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Korean literature abroad

In The Korea Times Claire Lee profiles LTI Korea director Kim Seong-kon, as he: 'speaks about the institution's current and future projects', in 'Understanding of classic literature required to understand contemporary literature' -- occasioned also by the recent publication of: 'a five-volume series of English translations of classic Korean literature in collaboration with The Korea Herald', which she introduces in a separate article, Murder, jealousy and lust.

The collaboration with Dalkey Archive Press, the Library of Korean Literature-series -- several volumes of which are already under review at the complete review, most recently Jang Eun-jin's No One Writes Back -- is mentioned, but Kim also has bigger plans:Starting next year, he is to make more pitches to overseas publishers, including Random House, Harper & Row and Simon & Schuster, to publish English translations of Korean literature.(I'm not sure who is advising him or where he gets his information, but 'Harper & Row' hasn't been the name of the publisher for nearly a quarter of a century, since the News Corp takeover of 1990 .....)

"Once published by these publishers, it becomes relatively easier to get reviews from the major media outlets (in the U.S.) and more likely for the books to receive attention," Kim said.

Interesting, too, to hear that:Up until this year, LTI Korea has been sending fully translated texts to foreign publishers instead of short summaries.(Of course, it's sad that American editors have to rely on served-up-to-them English translations to get any insight into the titles (i.e. that essentially none of them can read any of these languages).)

"We realized that takes too much time, energy and money," he said. "So we decided to just translate highlights from each novel and provide a brief summary. We think it'll be much more efficient and more appealing to overseas editors."

Also interesting:Kim also wants to see Korea's prominent authors have well-known translators who work exclusively with them and their works. Many celebrated Asian writers, including Haruki Murakami, Mo Yan and late Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata, each worked or are working with a single translator for English editions of their works, Kim said.Of course, that's an oversimplification -- and in Murakami's case flat-out not true, as Alfred Birnbaum and Philip Gabriel have certainly translated their fair share. (And having recently read Kawabata's The Sound of the Mountain in Seidensticker's translation, I can only say that those have gotten very creaky.)

[...]

"Most of Kawabata's works were translated by Seidensticker," said Kim. "For Haruki Murakami, there is Jay Rubin of Harvard University. For Mo Yan, there is Howard Goldblatt. We need more excellent translators (working exclusively) for Korean writers and their works."

Still, it's good to see someone who is obviously very pro-active and trying out a lot of things -- indeed, there are a hell of a lot of countries that I wish were similarly active.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Vietnamese literature in ... France

Tuoi Tre News profiles Doan Cam Thi, The 'matchmaker' of VN literature and the Francophone community, providing some insight into Vietnamese literature in France.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Literary Review Bad Sex in Fiction Award

They've announced that The City of Devi, by Manil Suri, has won the 2013 Literary Review Bad Sex in Fiction Award.

I'm just relieved I haven't reviewed it yet, as I've dealt with too many of the recent winners (last years' -- Infrared, by Nancy Huston -- and 2009 winner The Kindly Ones, by Jonathan Littell).

But if you want to get a taste of Suri's prose, get your copy of The City of Devi at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk. (The dismal sales-ranks at the Amazons suggest the prize does not have a great positive influence on sales.)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

The Restoration Game review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Ken MacLeod's The Restoration Game -- a nice little surprise I picked up at the library; certainly an author that has piqued my interest.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Publisher profiles: And Other Stories - Text Publishing

Writing in ... Cambodia | Geoffrey Hill Oxford lecture

Publisher profile: And Other Stories

At Africa in Words Katie Reid reports on Publishing a 'Double Negative': And Other Stories' UK/US publication of Ivan Vladislavić.

Vladislavić's novel -- recently reviewed here -- is just among the latest titles in And Other Stories' increasingly impressive list -- worth a closer look.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Publisher profile: Text Publishing

At BookBrunch Text Publishing publisher (and The Ern Malley Affair-author) Michael Heyward discusses: 'how an editorially led Australian independent is going international', in Good, old-fashioned Text.

An interesting look at an unusual publishing/writing-market -- as also: "Even 20 years ago, an Australian book was an exotic item on the international rights market" -- and it's impressive how they've established themselves very nicely, with a roster of authors any international publisher would be pleased to have. And their Text Classics line -- "milestones in the Australian experience" -- is also a great idea -- as is international distribution, which means you can actually find some of these in your US/UK bookshops. (They were also kind enough to send me some of these, so reviews will be up of a few of these titles soon (beginning, of course, with Patrick White's Happy Valley).)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Writing in ... Cambodia

In The Phnom Penh Post Emily Wight profiles president of the Cambodia Librarians and Documentalists Association Hok Sothik in Bookish champion hopes to boost Cambodia's lost culture of reading, as they held the third Cambodia Book Fair over the weekend.

It's apparently difficult to drum up interest, as what literary culture there was obviously suffered greatly under the Khmer Rouge ("Books were used to make cigarettes. Teachers, authors and books were all destroyed, as was so much of an entire generation") and even now: "people aren’t very interested in books".

Among the projects working to change that is the Nou Hach Literary Journal, profiled in another piece in The Phnom Penh Post, by Cecelia Marshall, who reports that: Cambodian literary journal sees revival.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Geoffrey Hill Oxford lecture

Poet -- and Oxford Professor of Poetry -- Geoffrey Hill will give his first lecture of the 2013-14 academic year, 'Poetry and "The Democracy of the Dead"'. today at 17:30

Several of his lectures from previous years are available here for you to listen to (though alas two seem to have been lost to 'technical problems') -- well, well worthwhile.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

December issues | André Schiffrin (1935-2013)

Literature in ... Viet Nam | Perumal Murugan profile

December issues

Some nice winter treats to get you started with in December, as issues of a variety of online periodicals are now available with a load of great reading -- notably:

- Words without Borders' December issue features the Oulipo -- with a bonus section on: "New Writing from Sudan". Start of with Many Subtle Channels-author Daniel Levin Becker's introduction, and work your way through !

- The Winter 2014 issue of the Quarterly Conversation is packed with good stuff (though I think Steve Donoghue is way too kind regarding Pierre Michon's Rimbaud the Son ("Readers who surrender to the strange whorls and swirls of this book will be lifted out of themselves and thrilled and sometimes richly, lastingly disoriented" -- yeah, okay ...))

- The December issue of Open Letters Monthly -- which includes Our Year in Reading and Our Year in Reading Continues

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

André Schiffrin (1935-2013)

Noted publisher -- especially at Pantheon Books and then at the New Press, which he founded -- André Schiffrin has passed away; see Robert D. McFadden's obituary in The New York Times, André Schiffrin, Publishing Force and a Founder of New Press, Is Dead at 78.

Two of his books about publishing are under review at the complete review: The Business of Books and Words and Money.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Literature in ... Viet Nam

At VietNamNet Bridge they report that there seems to be a pretty widespread local consensus that in Viet Nam Quality literature in dramatic slump.

(Of course, Dương Thu Hương was, for example, one of the nominees for the 2014 Neustadt International Prize for Literature -- but maybe her work isn't quite what they have in mind, either .....)

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Perumal Murugan profile

In The Caravan, N. Kalyan Raman writes about 'The Kongunadu novels of Perumal Murugan', the Tamil author, in Boats against the Current, offering an interesting introduction into Tamil fiction historically, and then Perumal Murugan's work in particular.

Several of his works have been translated into English; get your copy of, for example, Seasons of the Palm from Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Favourite Scottish novel (of past 50 years) | Translating from ... Tamil

No One Writes Back review

Favourite Scottish novel (of past 50 years)

As Helen Croney writes at the Scottish Book Trust weblog, The Favourite Scottish Novel is Revealed as they took a poll: "to find the favourite Scottish novel of the last 50 years".

Over 8,800 votes were cast, and Trainspotting, by Irvine Welsh, beat out Lanark by Alasdair Gray, 833 votes to 750. (A more distant third, the somewhat surprising choice of ... Black and Blue, by Ian Rankin (well, choices were limited to one book per author, so presumably this one was taken as representative ...).)

Can't really argue with either Trainspotting or Lanark (both of which I read before I started this site, which is why they're not under review here).

Get your copy of Trainspotting at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

Translating from ... Tamil

In The Hindu Kausalya Santhanam has a Q & A with translator Lakshmi Holmström, 'Meanings aren't in dictionaries alone'.

Interesting that she finds:I think publishers take translation much more seriously than they did 20 or 30 years ago. A great many translations are well produced and with attractive covers. At least some publishers publicise their translation list well, and make certain that they are reviewed. But it is a fact of life, I think, that there will never be a wide readership for many -- or indeed most -- translations outside specialised university courses. But at least there is a readership there.Well, that's kind of depressing .....

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

No One Writes Back review

The most recent addition to the complete review is my review of Jang Eun-jin's No One Writes Back.

This is another in Dalkey Archive Press' new Library of Korean Literature-series -- and an interesting piece of work. It is, in many respects, an atypical Dalkey publication -- though since they gotten into this national literature series-business big time their offerings (in these areas) have become a bit more unpredictable: Ayşe Kulin, anyone ? (see their publicity page) an author whose other American publisher is ... AmazonCrossing ?

Dalkey have had books that I thought could do well as mass-market/airport-store titles -- Paul Verhaeghen's Omega Minor, for one. But this is something different, a bona fide crowd-pleaser that practically begs to be a book club selection. I'm surprised -- stunned -- no commercial publisher landed this one, which I think might be have been a better Korean title to try to break into the American market than the 2011 lead title, Shin Kyung-sook's Please Look After Mom.

The drawback of how it comes to market now is that that Dalkey imprint can be both a blessing and a curse -- and I'm not sure it'll find its natural audience here (especially in that look-alike-covered series -- which I think is great but might put off some readers). So, for example, as I write this, a few weeks after it came out, the Amazon.com page shows -- aside from a disappointing sales rank of 590,794 -- only six additional items under 'Customers Who Bought This Item Also Bought'..... The first three are also titles from this series, followed by Sonallah Ibrahim's That Smell and Notes from Prison (New Directions), Amsterdam Stories by Nescio (NYRB), and another Dalkey title, Edouard Levé's Autoportrait. Good stuff -- very good ! -- but also pretty serious stuff, from smaller publishers, and nothing near as popular fare as this has the potential to be.

And people buying No One Writes Back should be the ones who also bought the more prominently marketed Korean titles -- say Kim Young-ha's I Have the Right to Destroy Myself -- as well as, of course, Please Look After Mom (the number two most-also-bought title (after another of his own) for I Have the Right to Destroy Myself, for example.

Here's also a case-study regarding the power of (some) reviews: No One Writes Back has been shamefully under-covered (though admittedly that flooding-the-market-with-ten-volumes-at-once schedule is a challenge for reviewers), but it got a glowing review from Nicholas Lezard in The Guardian just over a week ago -- and look here, the UK Amazon page sports both a much healthier sales-rank (an impressive 7,194 as I write this) and the 'Customers Who Bought This Item Also Bought' list is much more diverse (and not at all Korean-centric -- surprisingly, it doesn't include any other Korean titles at this time).

(It also got a far less glowing review (scroll down) at Totally Dublin, but for now The Guardian review seems to have carried the day -- or at least influenced more book-buyers.)

Presumably, the titles in this series won't get all that much individual attention, reviewers at best lumping several (or all ?) together in omnibus reviews. It's too bad: as The Guardian recognized, this one certainly deserves to be looked at all on its own -- as do the others.

(Posted by: M.A.Orthofer) - permanent link -

previous entries (21 - 30 November 2013)

archive index

- return to top of the page -

© 2013 the complete review

Main | the New | the Best | the Rest | Review Index | Links